Elsewhere on this site you’ll find information about insulins that are specially-designed for speed. Insulin isn’t normally injected into the bloodstream, but into the layer of fat under the skin. This doesn’t flood your blood with insulin too quickly, but it also doesn’t exactly mimic the rate of insulin generation and absorption from a fully-working pancreas.

These new insulins trigger glucose uptake fast-enough to offset the delay in delivery caused by the way they’re injected. Because of their speed of action and (relatively) short duration of action they are superior for use in insulin pumps. Pumps, though, pre-date these “modern” insulin formulations, and pump users had superior results as compared to people injecting several times per day. We’ve studied some of the issues involved with this combination and have some advice for those who may be forced for a time to use older insulins, e.g. Humulin R or Novolin R in place of Humalog or Novolog.

Here at Type1News we’ve been fascinated by the reports of these early pump users’ impressive A1C readings. After much study and consideration we think we’ve arrived at an insight into why this worked so well. For safety we’re going to make you read through some basics before sharing.

make you read through some basics before sharing.

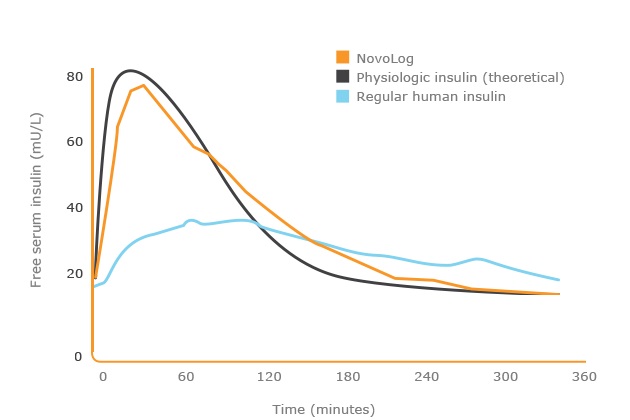

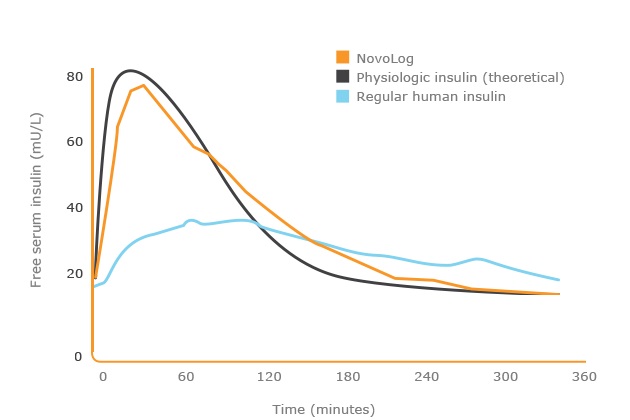

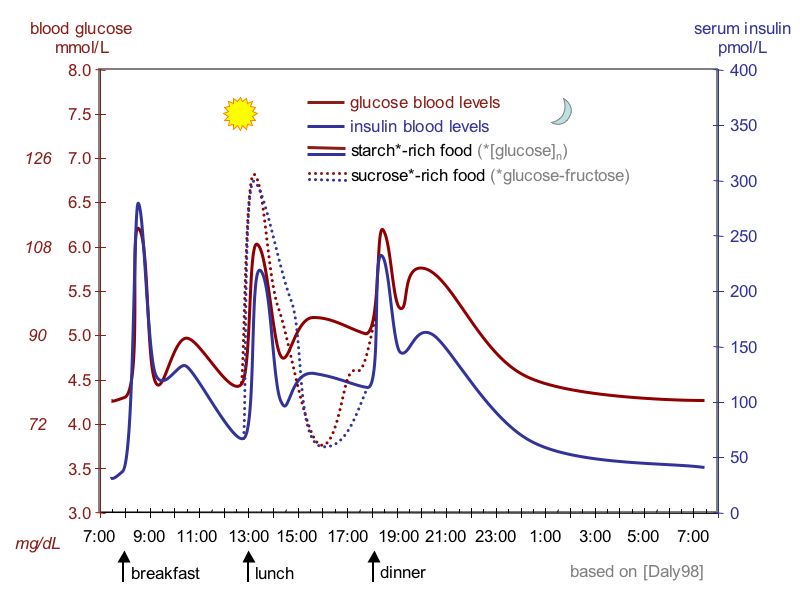

Before we start, it’s worth reviewing the action curves for Novolog (orange in the graph), for normal human pancreatic delivery to the liver (black), and regular human insulin by subcutaneous injection (light blue). Clearly “Regular” is an inferior insulin. We found it interesting, though, that this data is typically presented omitting the bottom 20 mU/L of free serum insulin. Such scale truncation is always suspicious in product literature – as it makes the difference in effect look greater than it actually is. Type1News.com may be the only place on the internet where you’ll find this graph presented with a linear scale. You can see that modern insulins are still far superior, but the difference is not as disastrous as other presentations may (mis)represent.

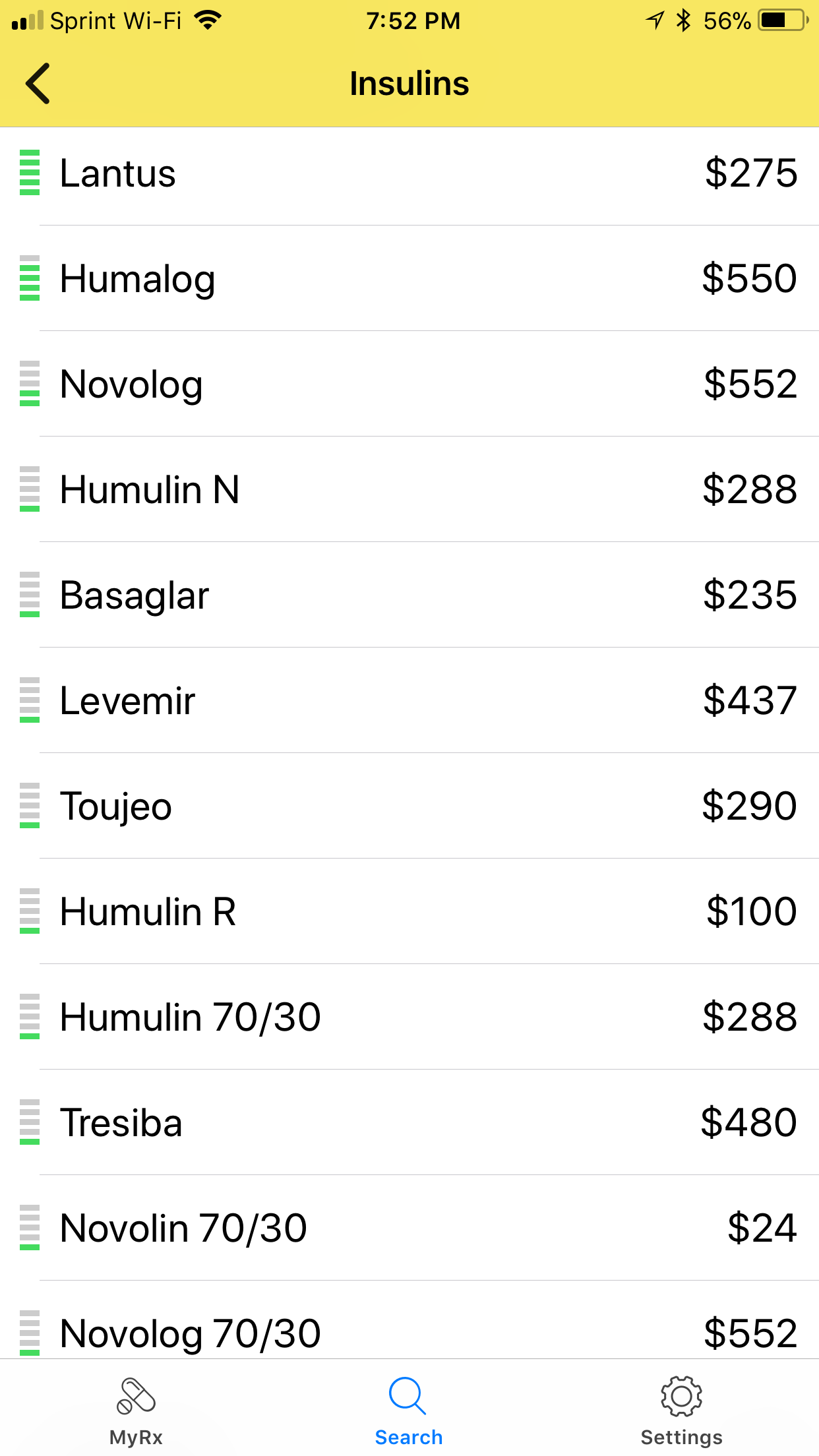

Before continuing, we want to emphasize again that the difference in price in the United States between Regular insulin and engineered Fast insulin is a result of politics and intellectual property law, not a result of different production and processing. Both Regular and Fast are produced in a miraculous recombinant DNA process. The yeast or other microbes involved have been engineered to produce a different molecule. Outside of the United States, these prices are far lower as are differences in price between formulations, eliminating any motivation to choose an inferior product.

For the purpose of discussion assume that Regular insulin is the only option. Let’s look at the implications.

Normally pump users have a basal “trickle” going all day and night and then manually trigger an all-at-once bolus dose at mealtime. Modern pumps deliver this basal not as a steady trickle, but at varying, customizable rates through the day, but always in the background at some rate. Consider the impact if a slower insulin is used for this basal dose. Regular insulins have an onset of action on the order of 30-45 minutes compared to 15 minutes for engineered Fast insulins. This is not a significant consideration for the basal, background, dose. The longer duration of action is also less significant for basal than for bolus delivery.

Normally pump users have a basal “trickle” going all day and night and then manually trigger an all-at-once bolus dose at mealtime. Modern pumps deliver this basal not as a steady trickle, but at varying, customizable rates through the day, but always in the background at some rate. Consider the impact if a slower insulin is used for this basal dose. Regular insulins have an onset of action on the order of 30-45 minutes compared to 15 minutes for engineered Fast insulins. This is not a significant consideration for the basal, background, dose. The longer duration of action is also less significant for basal than for bolus delivery.

If you ever consider using Regular in a modern pump, first ensure that you can “tell” the pump that the duration of action is much longer than with Fast insulin. Pumps do much of their magic by accounting for insulin that is still in the bloodstream but hasn’t yet been taken up. Users who in the past reported such good results with regular almost certainly had “tweaked” this duration setting with experience as to their own metabolism. Making adjustments on an emergency basis without this personal history is almost certain to have inferior results – another reason we emphasize that one should use Regular insulin only under the most dire circumstances. We just suspect that a properly adjusted pump can deliver superior results to periodic injection regardless of the insulin involved.

There is some suggestion that Humalog and Novolog are “buffered” differently or otherwise packaged in a way that is conducive to use in a pump. Some say Novolin R “precipitates” solids or otherwise clogs infusion sets. From our discussions with persons who’ve had diabetes for decades, we suspect that these issues with solids actually relate to Novolin N, a delayed uptake insulin delivery compound you can read about elsewhere. Still, another caution that using Regular has risks.

So Regular insulin isn’t a disaster for basal delivery in pumps. In fact, if you used a pump for just basal, Regular would probably be more than fine.

So here’s our insight into bolus dosing of regular insulin in a pump:

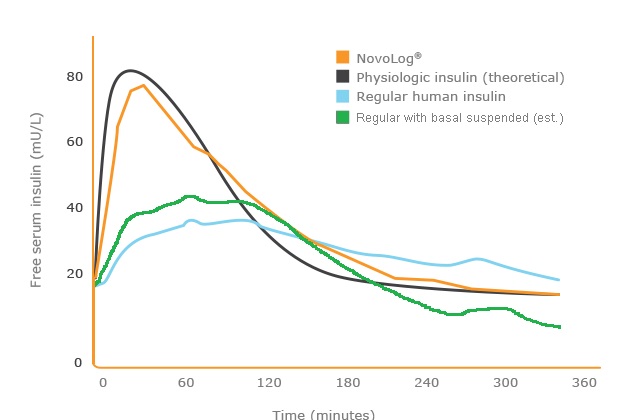

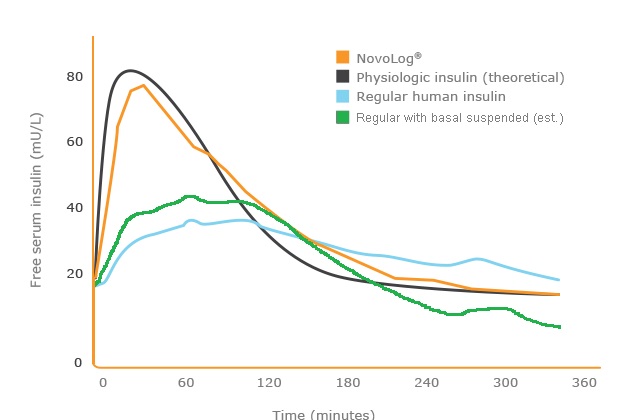

Consider the insulin uptake chart yet again. It suggests a basal presence of insulin of something like 15 mU/l. We can’t do a lot to speed the onset of Regular (delay eating as a compromise) but we can address the “hangover”  extended action by stopping basal delivery for a period after each meal, and adding that basal dose to the bolus. Think of it as “pulling the basal out from under” the lingering bolus dose. The undesirable extended action of the Regular actually serves as the basal between and after meals. Six or even eight hours after the last meal, basal delivery would resume, as the last of the day’s bolus doses are metabolized.

extended action by stopping basal delivery for a period after each meal, and adding that basal dose to the bolus. Think of it as “pulling the basal out from under” the lingering bolus dose. The undesirable extended action of the Regular actually serves as the basal between and after meals. Six or even eight hours after the last meal, basal delivery would resume, as the last of the day’s bolus doses are metabolized.

Adding the basal to the bolus raises the serum concentration of insulin at onset of the bolus, which somewhat offsets the slower insulin speed of onset. (The insulin in there is still working slower, but there’s more in there to work!) The green curve in the graph above attempts to show both the higher initial dose and the loss of the steady basal beneath. Again, we’re pulling the basal out from under the bolus curve. Let us know if you don’t understand the concept. It may be worth noting that – were the basal suspended for the other insulins as well, serum insulin levels would drop quicker in any case, but in practice a basal dose is usually left in place. This is either a basal schedule on a pump left in place for convenience’s sake, or a long-acting basal injected hours earlier.

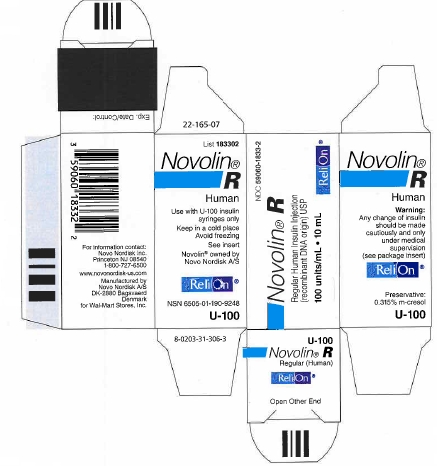

Again, none of this consideration would be necessary if it weren’t for the dramatic price difference between $265 per vial Novolog R and $25 per vial Relion Novolin R. This difference is essentially a political choice rather than a truth of chemistry. Still, if any of these insights help someone get by with Regular when there’s no option, we wish you the best possible results and believe there is reason for optimism. Please consult a medical professional and especially emphasize to them that you know how to adjust the duration of action setting in your pump. In truth, if you express to any medical professional that you’re considering Regular and they don’t find a way to provide you affordable access to fast insulin, I’d look for another healthcare provider.

make you read through some basics before sharing.

make you read through some basics before sharing. Normally pump users have a basal “trickle” going all day and night and then manually trigger an all-at-once bolus dose at mealtime. Modern pumps deliver this basal not as a steady trickle, but at varying, customizable rates through the day, but always in the background at some rate. Consider the impact if a slower insulin is used for this basal dose. Regular insulins have an

Normally pump users have a basal “trickle” going all day and night and then manually trigger an all-at-once bolus dose at mealtime. Modern pumps deliver this basal not as a steady trickle, but at varying, customizable rates through the day, but always in the background at some rate. Consider the impact if a slower insulin is used for this basal dose. Regular insulins have an  extended action by

extended action by

is Novolin, but in the past it’s been Humulin. They basically play Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk off against one another to keep that $24.88 price. At this price point Wal-Mart offers regular human insulin – Novolin R, they offer delayed reaction insulin, Novolin N, and they offer a 70/30 mix that creates an extended reaction similar to the extra post-meal bump seen in normal blood insulin levels. (Editor’s note, similarly re-branded Novolin formulations are now available for $25 at CVS, and see our posts elsewhere about pricing from GoodRx.)

is Novolin, but in the past it’s been Humulin. They basically play Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk off against one another to keep that $24.88 price. At this price point Wal-Mart offers regular human insulin – Novolin R, they offer delayed reaction insulin, Novolin N, and they offer a 70/30 mix that creates an extended reaction similar to the extra post-meal bump seen in normal blood insulin levels. (Editor’s note, similarly re-branded Novolin formulations are now available for $25 at CVS, and see our posts elsewhere about pricing from GoodRx.)