It may be that CGM’s – Continuous Glucose Monitors – are the area for greatest improvement in diabetes management. CGM’s involve a subcutaneous probe poked about 1/4 inch into the skin, essentially in the same fleshy layer into which insulin is injected. The probe is a soft plastic tube rather than a needle in the skin. Knowing how it resides in a fluid layer under the skin, we refer to this probe as the “wick.” It connects to an electronic device we call the “puck,” via little electric traces – just as a glucose tester connects to glucose strips. The puck has a bluetooth-style connection to an external monitor; either an insulin pump or a separate handheld device. Used with a pump, the system reports out blood glucose about once every 5 minutes, hence the term Continuous.

No matter who your device manufacturer is, they have a high monetary motivation to keep you happy with their system, so they liberally provide replacement CGM probes without additional cost.

This ability to collect ongoing data allows a sufficiently sophisticated pump or other monitor to make predictions about future blood glucose. Having collected user data for years, now, therapy manufacturers have developed sophisticated algorithms to predict low blood sugar and predict response to insulin under different circumstances.

When Medtronic first announced the CGM and pump combo used by my son, they branded the predictive app algorithms with IBM’s “Watson” AI brand. By the time the system was released, this branding was eliminated. Given our experience, I think IBM decided they didn’t want their brand possibly sullied by ultimately UNpredictable real-world results! Even with regular calibration, a CGM can easily be 20 to 40 points off. Even the best algorithm will fail given faulty inputs. Just ask the crew from 2001: A Space Odyssey!

The main point of this post is to warn you about the luck we have “installing” these CGMs. They get loaded into a spring-cocked “serter,” and poked into the abdomen – or for some folks, the back of the arm. As the wick goes into the skin, it is accompanied by a steel needle providing the structure for the flimsy wick to poke through. Once the needle is withdrawn there is sometimes bleeding. Although one can stop this bleeding by pressing on the external plastic frame for a period of minutes, the bleeding itself may compromise the install. The wick is not really designed to reside in free, possibly coagulating blood, and so it’s hard to bring the CGM to proper calibration. All this is to say that we have to discard nearly half of these CGM probes, despite our research into bleeding avoidance! No matter who your device manufacturer is, they have a high monetary motivation to keep you happy with their system, so they liberally provide replacement CGM probes without additional cost. Still, having to address a bleeding wound can be dispiriting, to say the least.

Another company, Dexcom, is currently marketing their CGM touting how long it can go without calibration – how many “finger sticks” it can eliminate. We have no experience with Dexcom, and it may indeed need little calibration, but in any tradeoff between accuracy and fewer finger sticks, WE choose accuracy. A sharp lancet, calibrated to the right depth, really doesn’t do lingering damage – so long as the fingertips are adequately cleaned with an alcohol swab! Given the long-term and short-term risks of insulin therapy based on inaccurate numbers, drawing a little blood is, so far, a worthy tradeoff.

Now, if the Dexcom has a higher insertion success rate, that’s another story. As Medtronic customers, we understand that the Dexcom probe goes in diagonally, so that part of the experience may be superior! We’re truly grateful to Medtronic for helping to keep our person with diabetes alive, so we nag them about few things. However, we believe the “closed systems” operated by device manufacturers…the non-interoperability…is a critical weakness, if not a moral offense. Let’s be magnanimous about the way we put this, rather than run anyone down: if Dexcom has a superior CGM but Medtronic has a superior pump, not being able to put these superior solutions together risks lives. We believe that the profit motive – wanting to guarantee sales of a whole system – gives all of these manufacturers a vested interest that may compromise their decision making!

So, algorithms aside, there’s room for improvement just getting data to the system. CGMs are literally lifesavers, alerting one to low or even pending low blood sugar. We would love to share the experiences of Dexcom customers, too, so – get in touch if you have a story to tell!

make you read through some basics before sharing.

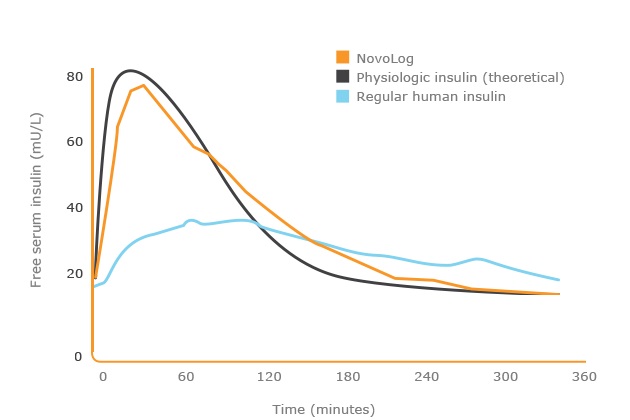

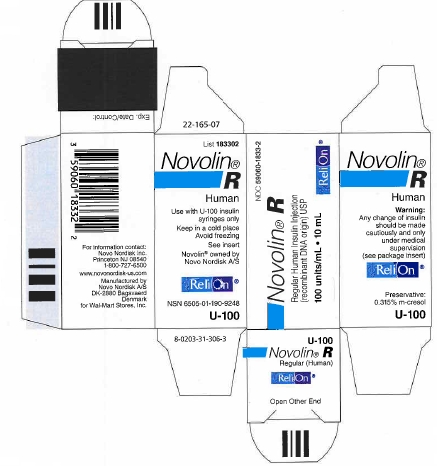

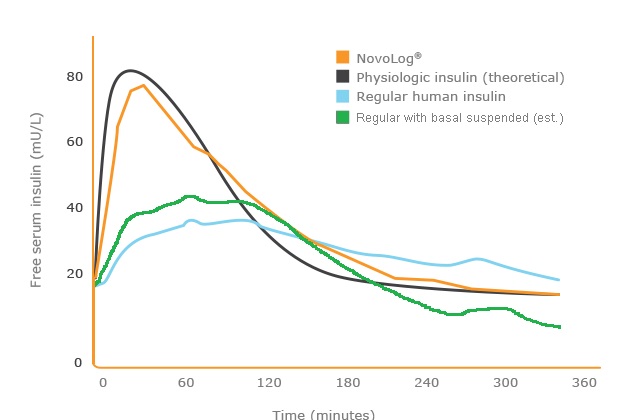

make you read through some basics before sharing. Normally pump users have a basal “trickle” going all day and night and then manually trigger an all-at-once bolus dose at mealtime. Modern pumps deliver this basal not as a steady trickle, but at varying, customizable rates through the day, but always in the background at some rate. Consider the impact if a slower insulin is used for this basal dose. Regular insulins have an

Normally pump users have a basal “trickle” going all day and night and then manually trigger an all-at-once bolus dose at mealtime. Modern pumps deliver this basal not as a steady trickle, but at varying, customizable rates through the day, but always in the background at some rate. Consider the impact if a slower insulin is used for this basal dose. Regular insulins have an  extended action by

extended action by

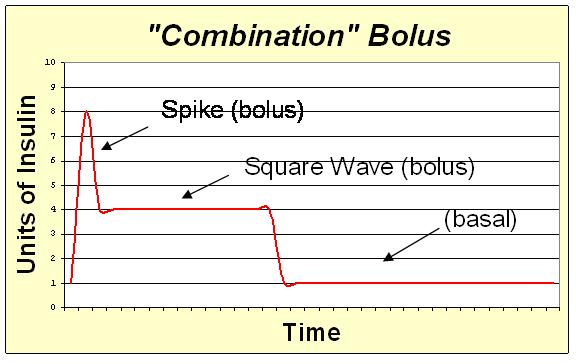

th what they call a dual-wave or Combination bolus, wherein one programs some percentage of your mealtime insulin to be delivered as an all-at-once bolus, but then an increased background dose to deliver the rest over a prolonged period. For extremely fatty foods or for even healthy foods with a high glycemic index (carbs digested slowly), one might program a so-called square wave delivery of insulin, simply taking that steady background dose to an elevated level for a time – with no real bolus at all!

th what they call a dual-wave or Combination bolus, wherein one programs some percentage of your mealtime insulin to be delivered as an all-at-once bolus, but then an increased background dose to deliver the rest over a prolonged period. For extremely fatty foods or for even healthy foods with a high glycemic index (carbs digested slowly), one might program a so-called square wave delivery of insulin, simply taking that steady background dose to an elevated level for a time – with no real bolus at all!